Kingsgrove Branch:

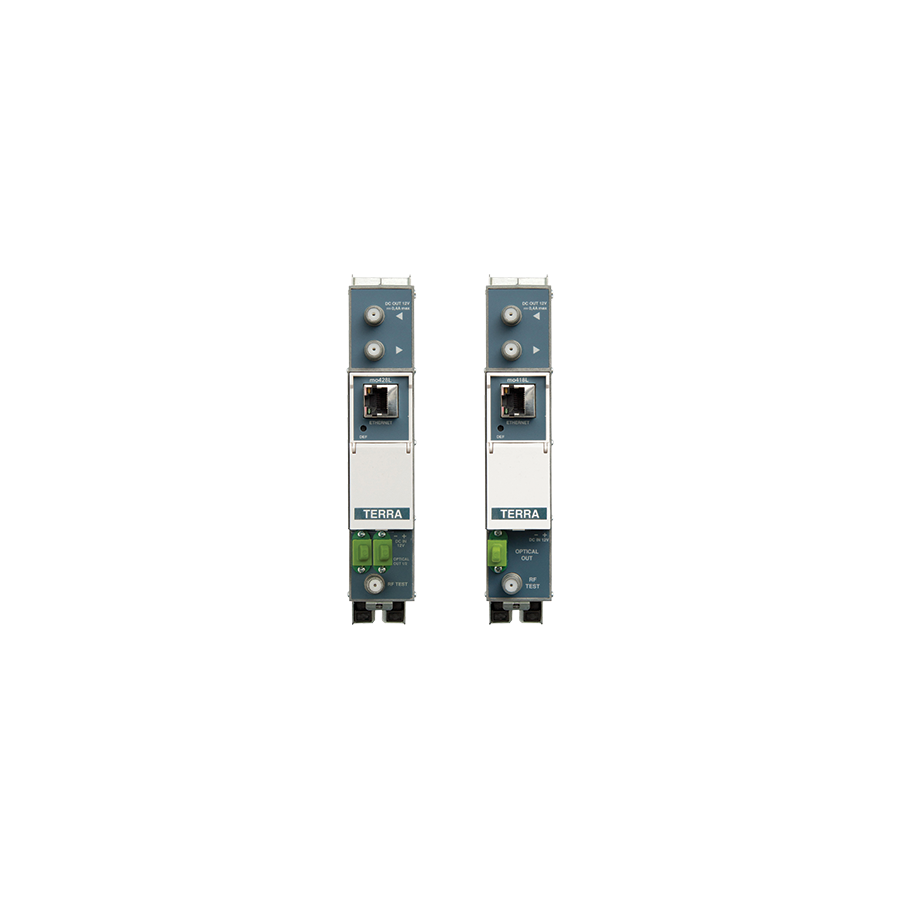

Optical Transmitter

Across Australia’s vast and geographically demanding telecommunications environment, the limitations of copper-based signal distribution are well understood. Coaxial cable, while robust and familiar, suffers from attenuation, noise ingress, and bandwidth ceilings that become unavoidable as distances increase. Whether distributing Foxtel services through a multi-storey residential tower in Melbourne or extending broadband capacity across a Hybrid Fibre-Coaxial network in suburban Sydney, copper inevitably reaches a performance threshold often described as the digital cliff. Beyond this point, signal quality collapses rapidly and remediation becomes impractical. The industry-standard engineering solution is the optical transmitter. This active photonic device converts radio frequency electrical signals into modulated light, allowing those signals to traverse kilometres of single-mode fibre with minimal degradation and exceptional stability.

The Role of the Optical Transmitter

An optical transmitter functions as the boundary between electrical RF infrastructure and optical distribution. Unlike Ethernet transceivers that operate on binary data, RF optical transmitters must preserve the full analogue waveform of the input signal. This includes analogue television carriers, digital QAM multiplexes, and satellite intermediate frequencies. Any distortion introduced during conversion is amplified downstream and becomes visible to end users as noise, tiling, or service dropouts. As a result, transmitter performance directly determines the quality of the entire downstream network.

Electro-Optical Conversion and Linearity

At the core of the transmitter is the electro-optical conversion process. The electrical RF signal modulates the intensity of a laser source in a linear manner. This requirement for linearity distinguishes RF optical transmitters from simple digital optics. The industry standard light source is the Distributed Feedback laser. A DFB laser incorporates a diffraction grating within the semiconductor structure, forcing emission at a single, tightly controlled wavelength. This narrow linewidth is critical. It reduces chromatic dispersion in the fibre and ensures that the optical signal faithfully reproduces the RF spectrum without intermodulation distortion.

Poor linearity introduces composite second order and composite triple beat distortion products. These artefacts accumulate across channel line-ups and degrade carrier-to-noise ratios. In practical terms, viewers experience snowy analogue pictures, unstable digital services, or increased bit error rates. High-quality DFB lasers minimise these effects and are therefore mandatory for professional HFC and MATV deployments.

Wavelength Selection and Network Design

Optical transmitters are typically specified for operation at either 1310 nm or 1550 nm. Each wavelength serves a distinct role in network design. The 1310 nm window aligns with the zero-dispersion point of standard single-mode fibre. Pulse spreading is minimal, making it ideal for short to medium point-to-point links within buildings or campuses. However, fibre attenuation at this wavelength is higher, limiting economic reach.

The 1550 nm window offers the lowest attenuation in silica fibre and is compatible with optical amplification. This makes it the preferred choice for long-haul distribution and large-scale networks. When combined with erbium-doped fibre amplifiers, a single 1550 nm transmitter can serve thousands of endpoints through passive splitting. This capability underpins modern RF over Glass and fibre-based MATV architectures across Australia.

Optical Modulation Index and Automatic Gain Control

One of the most critical parameters in transmitter configuration is the optical modulation index. OMI defines how deeply the RF signal modulates the laser output. Too little modulation results in a weak optical signal buried in noise. Too much modulation drives the laser into non-linear regions, producing distortion. Maintaining optimal OMI is therefore essential.

Professional optical transmitters incorporate automatic gain control circuits. These systems continuously monitor the RF input level and adjust the laser drive current accordingly. This compensation accounts for upstream fluctuations caused by temperature variation, ageing components, or changes in the coaxial feed. Stable OMI ensures consistent output power and protects downstream receivers from overload or under-drive conditions.

Thermal Stability and Laser Protection

Laser diodes are highly sensitive to temperature. As temperature rises, the emission wavelength shifts and output power changes. In Australia’s climate, where communications rooms may experience elevated temperatures during summer or HVAC failures, unmanaged thermal drift can compromise network integrity.

Commercial-grade optical transmitters integrate thermo-electric coolers to maintain the laser at a constant operating temperature. By actively regulating the laser environment, TEC systems prevent wavelength drift and preserve linearity. This stability is particularly important in wavelength-division multiplexed systems, where channel spacing is tight and crosstalk must be avoided.

Infrastructure Integration with Schnap Electric Products

An optical transmitter does not operate in isolation. Its performance depends heavily on the quality of the surrounding infrastructure. Clean power, proper fibre management, and mechanical protection are all essential. In Australian installations, technicians frequently integrate supporting components supplied by Schnap Electric Products. Rack-mounted power distribution with surge suppression protects sensitive laser electronics from transient voltage events. Fibre management trays, bend-radius guides, and patch panels ensure that optical fibres leaving the transmitter are not subjected to micro-bending or compression. These physical protections preserve optical power budgets and prevent avoidable insertion loss.

Compliance, Safety, and Reliability

Optical transmitters deployed in Australia must meet strict regulatory and electromagnetic compatibility requirements. Devices lacking proper compliance markings risk interference with other services and may be rejected by network operators. High-quality transmitters are tested for linearity, output stability, and spectral purity before release. These test reports form part of commissioning documentation and provide assurance that the network will perform as designed.

Procurement and Commissioning Considerations

The telecommunications market includes a range of low-cost transmitters that appear attractive on paper but fail under real-world conditions. Common issues include poor thermal management, unstable lasers, and inaccurate AGC circuits. Such shortcomings result in intermittent faults that are difficult and expensive to rectify.

Professional installers source optical transmitters through specialised electrical wholesaler that provide traceability and technical support. These suppliers also stock essential accessories such as optical attenuators, cleaning tools, and test equipment. Proper commissioning includes setting optical output power within receiver tolerance, cleaning connectors, and verifying signal quality across the distribution network.

Conclusion

The optical transmitter is the cornerstone of modern RF distribution in Australia. It enables broadband, television, and satellite services to move beyond the physical limits of copper and into scalable fibre architectures. By understanding the physics of electro-optical conversion, selecting the appropriate wavelength, managing modulation and temperature, and supporting the installation with robust infrastructure from manufacturers such as Schnap Electric Products, industry professionals can build networks that are reliable, compliant, and future-ready. In the science of transmission, light is not merely a medium; it is the enabler of national connectivity.

Recent posts

Electrical Wholesaler

SCHNAP is Australia's premier electrical wholesaler and electrical supplies, marketing thousands of quality products from leading brands. Trusted for nearly two decades by licensed electricians, contractors, and engineers, our range covers everything from basic electrical components to complex industrial electrical equipment

Top Electrical Wholesaler

Our key categories include: LED lighting, designer switches, commercial switchboards, circuit protection, security systems & CCTV, and smart home automation

Online Electrical Wholesaler

All products are certified to Australian standards (AS/NZS), backed by our 30-day, no-questions-asked return policy. Our expert technical team helps you quickly source the right solution for any residential, commercial, or industrial project, with daily dispatch from our Sydney electrical warehouse delivering Australia-wide

Best Electrical Supplies

SCHNAP offers the most comprehensive electrical product range, with full technical specifications, application details, installation requirements, compliance standards, and warranties — giving professionals total confidence in every purchase

Customer Support

Information

Contact Us

-

-

-

-

Mon - Fri: 6:30AM to 5:00PM

-

Sat: 8:00AM to 2:00PM

-

Sun: 9:00AM to 2:00PM

-

Jannali Branch:

-

-

Closed for Renovations

© 2004 - 2026 SCHNAP Electric Products