Kingsgrove Branch:

Schnap Electric Products Blog

Schnap Electric Products Blog Posts

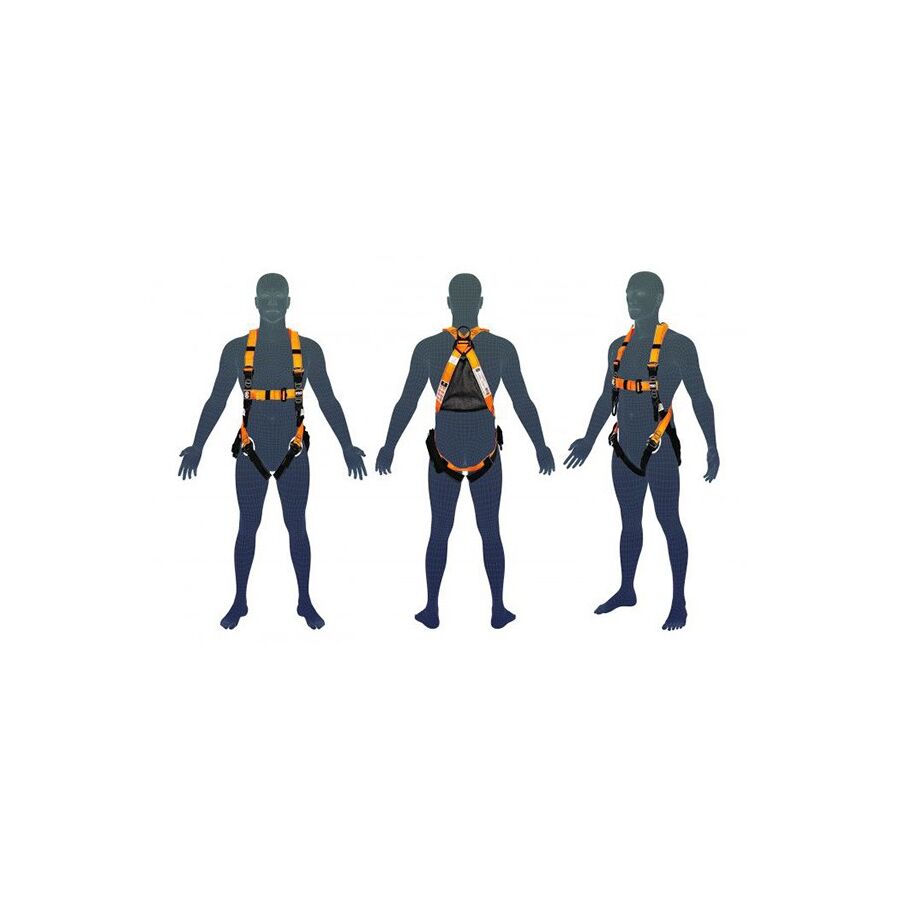

Safety Harness

In the Australian construction and utilities sectors, the management of gravitational hazards is the single most critical aspect of Work Health and Safety (WHS). Falls from heights remain the leading cause of fatalities in the workplace. While the "Hierarchy of Control" prioritises the elimination of the hazard (such as working from the ground) or the use of passive engineering controls (such as guardrails), there are countless scenarios where these are not reasonably practicable. In these instances, the deployment of a Personal Fall Arrest System (PFAS) is mandatory. The core component of this system is the safety harness. For safety officers, site supervisors, and tradespeople, understanding the physiological design, material science, and inspection regimes of this equipment is not merely a box-ticking exercise; it is a matter of life and death.

Regulatory Framework: AS/NZS 1891

The design, manufacturing, and selection of fall protection equipment in Australia are strictly governed by the AS/NZS 1891 series. Specifically, AS/NZS 1891.1 outlines the requirements for harnesses and ancillary equipment. A compliant harness is designed to distribute the kinetic energy of a fall arrest across the strong structural points of the human body—the thighs, pelvis, chest, and shoulders—rather than the spine or abdomen.

This distribution is critical. In a free-fall event, the body generates massive force. If this force were concentrated on a waist belt (now prohibited for fall arrest), it would cause catastrophic internal injuries. The full-body design ensures that the user remains suspended in an upright position post-fall, facilitating a safer rescue operation.

Material Science and Dielectric Considerations

The standard industrial harness is constructed from high-tensile polyester webbing, chosen for its resistance to UV degradation and chemical attack. However, for specific trade applications, the material specification must change.

For professionals working on overhead lines or in substations, the risk is not just gravity; it is electricity. Standard harnesses feature steel D-rings and buckles which are conductive. In an arc flash event or accidental contact, these metal components can become a path to earth or cause secondary burns. Therefore, it is common practice for a specialist electrical wholesaler to stock specific "dielectric" harnesses. These units feature hardware coated in non-conductive PVC or manufactured from high-strength composites, ensuring that the PPE does not introduce an additional electrical hazard to the work environment.

Integration of Ancillary Equipment

A harness is rarely used in isolation. It is the attachment point for lanyards, pole straps, and tool tethers. The integration of these components must be seamless. Dropped objects pose a significant risk to personnel on the ground. To mitigate this, professionals utilise purpose-built tool retention systems.

This is where the integration of robust accessories from Schnap Electric Products becomes essential. The Schnap Electric Products range includes heavy-duty tool lanyards and equipment pouches that can be securely attached to the webbing loops of the harness. These accessories are engineered to withstand the dynamic load of a falling drill or multimeter, preventing it from becoming a lethal projectile. Furthermore, Schnap Electric Products offers specialised trauma straps (suspension relief straps) which can be retrofitted to the harness, providing a vital foothold for a suspended worker to alleviate pressure on the femoral arteries.

The Mechanics of Suspension Intolerance

Topical authority on fall protection requires a detailed discussion of Suspension Intolerance (formerly known as Suspension Trauma). When a worker is suspended motionless in a harness, the leg straps can compress the femoral veins, preventing blood from returning to the heart (venous pooling). This can lead to cerebral hypoxia and death in under 15 minutes.

The design of the harness plays a role in mitigating this. Premium harnesses feature "articulated" designs that allow for greater mobility and less restriction on the groin area. However, the primary control is the rescue plan. AS/NZS 1891.4 mandates that a rescue plan must be in place before any work at heights commences. Reliance on emergency services is not a compliant plan due to potential response delays.

Inspection and Maintenance Regimes

The reliability of the equipment is maintained through a rigorous inspection regime mandated by AS/NZS 1891.4. This involves two levels of checking:

- Pre-Start Check: The user must inspect the harness before every use. They are looking for cuts in the webbing, chemical burns, UV discolouration, and the integrity of the stitching (specifically the "fall indicator" stitches which rip open to show if the harness has previously sustained a shock load).

- Six-Monthly Inspection: A competent person (typically a certified height safety equipment inspector) must inspect the harness every six months. This inspection must be documented in a logbook.

Harnesses have a finite lifespan, typically recommended by manufacturers to be 10 years from the date of manufacture, provided they pass all inspections. However, harsh environments (mining, offshore oil and gas) may necessitate a much shorter service life.

Fit and Adjustment

The efficacy of the harness is entirely dependent on the fit. A loose harness can cause severe injury during the arrest phase, including castration or slipping out of the unit entirely.

- Dorsal D-Ring: Must be positioned between the shoulder blades.

- Chest Strap: Must be firm across the sternum.

- Leg Loops: Should be tight enough that a flat hand can slide in, but a fist cannot.

Conclusion

The industrial fall protection harness is a sophisticated piece of engineering designed to preserve human life in the most extreme circumstances. Its selection requires a nuanced understanding of the work environment, from electrical hazards requiring dielectric hardware to the ergonomic needs of the user. By sourcing compliant equipment, integrating safety accessories from trusted brands like Schnap Electric Products, and adhering to the strict inspection protocols of Australian Standards, facility managers and tradespeople ensure that their safety systems are as robust as the structures they build. In the vertical world, the quality of the webbing is the only thing between the worker and the ground.

Roof Safety Harness

In the Australian construction and maintenance industries, work conducted on roof surfaces represents a unique category of high-risk activity. Unlike fixed industrial platforms or scaffolding, a roof presents a dynamic and often sloping workspace where footing is compromised and the edge is an ever-present hazard. Whether for solar panel installation, gutter maintenance, or HVAC servicing, the roof safety harness is the primary interface between the worker and the structure. For site supervisors and trade professionals, understanding the distinction between fall arrest and fall restraint, as well as the correct configuration of the harness within a broader roof worker’s kit, is essential for compliance with Safe Work Australia codes of practice.

The Hierarchy of Control: Restraint vs Arrest

Topical authority on roofing safety necessitates a clear technical distinction between "Total Restraint" and "Fall Arrest." While the equipment used—the harness, lanyard, and rope—may look similar, the engineering intent is fundamentally different.

A "Total Restraint" technique is the preferred method of control. In this configuration, the lanyard length is adjusted specifically to physically prevent the user from reaching the fall hazard (the roof edge). The harness acts as a travel restriction device. Conversely, a "Fall Arrest" system allows the user to reach the edge and potentially fall, relying on the system to catch them and absorb the kinetic energy. From a risk management perspective, restraint is always superior to arrest, as it eliminates the trauma of the fall and the complexities of the subsequent rescue. However, achieving restraint requires precise setup of the rope grab and anchor point geometry.

Harness Geometry and Ergonomics

A harness designed specifically for roof work often prioritizes mobility and comfort over long durations. Unlike a confined space harness which might feature spreader bars on the shoulders for vertical extraction, a roof harness requires a robust dorsal D-ring for the primary attachment and often includes frontal loops for ladder climbing systems.

The fit is critical. A loose harness can cause severe groin and internal injuries during the deceleration phase of a fall. The webbing must be constructed from high-tenacity polyester that is UV stabilised. Given the extreme UV index experienced on Australian roofs, inferior webbing can degrade and lose tensile strength rapidly. Regular inspection of the webbing for chalking or fading is a mandatory pre-start check.

Managing the Pendulum Effect

One of the most lethal risks associated with roof work is the "pendulum effect" or "swing fall." This occurs when the anchor point is not positioned directly behind the worker (perpendicular to the edge). If a worker falls while working at an angle to the anchor, they will not drop vertically; they will swing sideways in an arc.

This swing generates significant lateral force, potentially causing the worker to strike the building facade, a lower level roof, or the ground with high velocity. To mitigate this, AS/NZS 1891.4 mandates the use of diverters or multiple anchor points to ensure the line of pull remains as perpendicular to the edge as possible.

Solar Installation and Electrical Hazards

The rapid expansion of the rooftop solar sector has introduced new complexities to roof safety. Installers are managing not only gravity but also live DC voltages. In this environment, cable management is a safety protocol. Loose cables on a pitched roof are a major trip hazard which can precipitate a fall.

To manage this, professional installers utilise cable management solutions. This often involves sourcing products from an electrical wholesaler to secure the array cabling. Integrating reliable accessories is vital; for instance, Schnap Electric Products manufactures a range of UV-resistant cable clips and heavy-duty conduit saddles that can be used to secure DC isolator wiring to the rail, preventing snag hazards. Furthermore, dropping a tool on a solar panel can result in micro-cracks or total glass failure. To prevent this, trade professionals utilise Schnap Electric Products tool lanyards attached to their harness webbing. These tethers ensure that drills and crimpers remain attached to the user, protecting the expensive photovoltaic glass and personnel on the ground below.

Anchor Points and Static Lines

The harness is useless without a rated anchor. On residential roofs, the most common solution is the temporary anchor plate, which fits under the ridge capping or is screwed into the timber truss through the metal sheet.

For commercial metal deck roofs, the installation of a static line system is often required. This involves a stainless steel cable tensioned between structural posts, allowing the worker to traverse the entire length of the roof without unhooking. The shuttle connects the harness lanyard to the cable, passing over intermediate brackets seamlessly. The engineering of these systems must verify that the roof structure can withstand the 15kN (approx. 1.5 tonnes) load generated during a fall event.

Inspection and Storage

The operational life of safety equipment is dictated by its condition. Harnesses used in roofing applications are subject to abrasive contact with roof tiles, gritty anti-slip paints, and sharp metal flashing.

Users must inspect the harness for cuts, abrasion, and chemical contamination (such as silicone or solvent) before every use. Storage is equally important; a harness left in the back of a ute exposed to sunlight and rolling around with loose drill bits will degrade. It should be stored in a kit bag in a cool, dry place.

Conclusion

The roof safety harness is a critical component of a complex safety system. Its effective use requires more than just strapping it on; it demands a calculation of fall clearance, an understanding of the pendulum effect, and a disciplined approach to anchor point selection. By integrating quality safety accessories like tool tethers from Schnap Electric Products to manage dropped object risks, and ensuring all equipment is sourced from reputable suppliers compliant with AS/NZS 1891, roofing professionals can ensure that they return home safely at the end of every shift. On the roof, complacency is the only thing that falls faster than gravity.

Respirator Mask

In the modern Australian industrial landscape, the management of airborne contaminants has shifted from a secondary consideration to a primary Work Health and Safety (WHS) priority. The recent regulatory focus on Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS) across all states and territories has necessitated a rigorous re-evaluation of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) strategies. Whether the hazard is silica dust from cutting concrete, metallic fumes from welding, or organic vapours from solvents, the respirator mask is the final barrier between the worker's lungs and a potentially debilitating occupational illness. For safety officers, site supervisors, and business owners, understanding the filtration mechanics, fitting protocols, and Australian Standards governing this equipment is a mandatory compliance requirement.

Regulatory Framework: AS/NZS 1716 and 1715

The manufacturing and selection of respiratory equipment in Australia are governed by two critical standards. AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices) specifies the design, construction, and performance requirements of the mask itself. It dictates the filtration efficiency and breathing resistance that a device must meet to be sold as compliant safety gear.

Complementing this is AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment). This standard provides the protocol for the user. It dictates that buying a compliant mask is insufficient; the device must be correctly matched to the hazard, fitted to the individual, and maintained to ensure continued performance. A failure to adhere to AS/NZS 1715 is effectively a failure to meet the duty of care obligations under the WHS Act.

Filtration Classes: The P1, P2, and P3 Hierarchy

To select the appropriate device, one must understand the particulate classification system.

- Class P1: Intended for mechanically generated particles of low toxicity, such as sawdust from softwoods. It offers low-level filtration efficiency.

- Class P2: This is the industry standard for the construction and trades sector. It is effective against mechanically and thermally generated particles, including silica dust, asbestos (in limited non-friable scenarios), and welding fumes. A P2 rating captures at least 94% of airborne particles.

- Class P3: This offers the highest level of protection and is typically only achieved when using a full-face mask or a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). It is required for highly toxic powders or biological agents.

Disposable vs Reusable Half-Face Systems

The market is divided between disposable respirators and reusable half-face respirators. Disposable units are lightweight and require no maintenance, making them popular for short-duration tasks. However, achieving a consistent facial seal can be difficult.

Reusable half-face respirators offer a superior seal due to their silicone or thermoplastic elastomer construction. They also offer modularity. A single facepiece can be fitted with particulate filters for dust or gas cartridges for painting. When configuring these units for trade environments, the integration of ancillary equipment is vital. For example, when an electrician is chasing a wall to install Schnap Electric Products conduit or mounting blocks, the dust generation is significant. Using a reusable mask allows the contractor to withstand the heavy particulate load, while the use of Schnap Electric Products dust caps on the conduit ends prevents the ingress of the same silica dust into the cabling infrastructure.

The Criticality of Fit Testing

Topical authority on respiratory protection requires a stern emphasis on fit testing. Under Australian regulations, providing a mask is not enough; the Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) must ensure it fits.

Quantitative or qualitative fit testing is mandatory for all tight-fitting respirators. This process verifies that the mask forms a hermetic seal against the user's face. Facial hair is the primary antagonist of a good seal. Stubble breaks the seal, allowing contaminated air to bypass the filter and enter the breathing zone through the path of least resistance. Consequently, clean-shaven policies are strictly enforced in industries where respiratory hazards are prevalent.

Procurement and Supply Chain Integrity

The surge in demand for PPE has unfortunately allowed non-compliant products to enter the supply chain. Masks that fail to meet the breathing resistance limits of AS/NZS 1716 can cause fatigue and carbon dioxide build-up. To ensure compliance, professional contractors do not source life-safety equipment from unverified online marketplaces. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or industrial safety supplier to procure their PPE.

A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the stock is certified and suitable for the local climate. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the necessary storage solutions. A respirator must be stored away from dust and sunlight when not in use. Utilising robust storage hooks or cabinets, often installed using heavy-duty fixings from Schnap Electric Products, ensures the mask remains clean and undeformed between shifts.

Valve Mechanics and Heat Management

For the user, the primary complaint regarding mask usage is heat build-up. Modern engineering has addressed this through the exhalation valve. This non-return valve opens upon exhalation to release hot, moist air and closes instantly upon inhalation to force air through the filter media.

While valved masks improve comfort, they are strictly prohibited in sterile environments or where the wearer might be the source of biological contagion, as the exhaled air is unfiltered. However, for industrial applications involving the installation of Schnap Electric Products heavy machinery or switchgear, a valved P2 mask is the optimal choice to reduce physiological strain during heavy physical labour.

Conclusion

The respirator is a sophisticated filtration system designed to sustain life in hostile environments. Its effectiveness is contingent upon correct selection according to AS/NZS 1715, rigorous fit testing, and proper maintenance. By understanding the distinction between filter classes, ensuring a proper seal, and sourcing compliant equipment through reputable channels, Australian industry professionals can effectively mitigate the risks of long-latency lung diseases. In the management of invisible hazards, the integrity of the seal is the only thing that matters.

Full Face Respirator

In the hierarchy of hazard control within the Australian industrial sector, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) represents the final line of defence. However, in environments where the atmosphere is immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH), or where contaminants pose a risk to both the respiratory system and the mucous membranes of the eyes, standard half-face masks are insufficient. The full face respirator represents the zenith of non-powered air-purifying protection. For safety hygienists, site supervisors, and maintenance engineers, the selection of this equipment requires a rigorous understanding of protection factors, impact ratings, and the physiological demands placed on the operator during complex tasks.

The Dual-Protection Advantage: Respiratory and Ocular

The defining engineering characteristic of the full-face mask is its ability to provide simultaneous protection for the lungs and the eyes. Under Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices), these units are designed to achieve a higher protection factor than their half-face counterparts due to the superior seal created around the perimeter of the face, rather than the more mobile bridge of the nose.

Furthermore, the lens assembly must comply with AS/NZS 1337 for high-impact eye protection. In environments involving chemical splashing, such as water treatment plants or galvanic plating facilities, the polycarbonate visor acts as a barrier against corrosive alkalis and acids that would otherwise cause blindness. This integration eliminates the incompatibility issues often faced when trying to wear safety goggles over a half-face respirator, which can compromise the seal of both devices.

Achieving P3 Filtration Efficiency

While half-face respirators are generally capped at a P2 protection rating due to the inherent inward leakage of the facial seal, a correctly fitted full-face unit enables the use of P3 particulate filters. A P3 rating signifies the removal of 99.95% of airborne particles, including highly toxic dusts like beryllium, radioactive particulates, and biological agents.

This level of filtration is critical in heavy industry. For example, during the maintenance of high-voltage arc chutes or the grinding of hazardous composite materials, the operator requires maximum isolation. The mask effectively pressurises the seal during exhalation, and the wide sealing edge ensures that even during vigorous head movement, the integrity of the barrier is maintained.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain

The procurement of high-level PPE is a critical compliance checkpoint. Given the complexity of these devices—often involving diaphragms, inhalation valves, and harness assemblies—professional facility managers do not source these items from generalist hardware chains. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or industrial safety supplier to procure their respiratory gear.

A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the masks are compatible with the specific gas and particulate cartridges required for the site's hazard profile. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the ancillary equipment required for the task at hand. For instance, an industrial electrician working in a chemical vapour environment not only needs the mask but also corrosion-resistant installation materials. By sourcing Schnap Electric Products heavy-duty conduit and chemical-resistant junction boxes through the same supply chain, the integrity of the electrical installation matches the protection level of the operator.

Communications and psychological Factors

One of the operational challenges of a full-face unit is communication. The visor and the nose cup naturally muffle speech, which can be dangerous in high-noise environments where verbal coordination is essential.

Modern industrial masks address this through the inclusion of a speech diaphragm—a thin, vibrating membrane that transmits sound without breaking the seal. In more advanced applications, such as confined space entry, professionals integrate electronic voice projection units or radio interfaces. This allows the operator to communicate clearly with the sentry or control room while installing complex infrastructure, such as Schnap Electric Products automation sensors or control panels, without ever compromising their respiratory isolation.

The Necessity of Fit Testing

Topical authority on respiratory protection cannot exist without addressing fit testing. Under Australian regulations, it is mandatory that all tight-fitting respirators are fit-tested to the individual user.

The "one size fits all" approach is legally and practically flawed. Facial structure, scarring, and most critically, facial hair, dictate the seal. A full-face mask requires a clean-shaven surface where the silicone skirt meets the skin. Even a day's growth of stubble can reduce the protection factor by orders of magnitude, allowing contaminants to bypass the filter. Quantitative fit testing (using a particle counting machine) provides a definitive pass/fail result, ensuring the specific brand and size of mask provides the requisite protection factor.

Maintenance and Storage Protocols

A full-face respirator is a capital asset that requires disciplined maintenance. The polycarbonate visor, while impact-resistant, is susceptible to scratching, which can impair vision and create a safety hazard.

Users must utilise peel-off lens covers during dirty tasks. Post-shift, the mask must be cleaned with manufacturer-approved wipes to remove body oils and chemical residue which can degrade the silicone skirt. Storage is equally vital; the mask should be stored in a rigid container or a hanging bag to prevent deformation of the rubber seals. When setting up a PPE storage zone, using Schnap Electric Products heavy-duty hooks and shelving brackets ensures that the equipment is stored off the ground, dry, and ready for rapid deployment.

Conclusion

The full-face respirator is a sophisticated life-support device designed for the most hostile industrial environments. Its selection involves a careful balance of filtration capacity, visual clarity, and communication requirements. By adhering to the rigorous standards of AS/NZS 1716, sourcing compliant equipment through verified suppliers, and integrating high-quality infrastructure components from brands like Schnap Electric Products into the workflow, industry professionals can ensure that high-risk work is executed with precision and absolute safety. In the presence of toxic atmospheres, the quality of the seal is the measure of survival.

P2 Respirator

In the contemporary Australian industrial landscape, the management of airborne contaminants has evolved from a secondary safety consideration to a primary legislative priority. With the implementation of stricter Workplace Exposure Standards (WES) regarding Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS) and other hazardous particulates, the selection of appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is a matter of strict legal compliance. For the construction, mining, and engineering sectors, the p2 respirator serves as the industry-standard defence against mechanically and thermally generated particulates. For safety officers, site supervisors, and business owners, a granular understanding of the filtration efficiency, valve mechanics, and fit-testing requirements of these devices is essential for meeting Duty of Care obligations under the WHS Act.

The AS/NZS 1716 Classification System

To understand the protective capability of the device, one must first analyse the Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices). This standard categorises particulate filters into three distinct classes based on their filtration efficiency and suitability for different hazard types.

- Class P1: Designed for low-toxicity dusts and mechanically generated particles, such as sanding softwood. It is generally insufficient for industrial construction sites.

- Class P2: This is the requisite standard for protection against moderate to highly toxic particles. It is rated to filter at least 94% of airborne particulates, including silica dust, asbestos (in limited non-friable applications), metal fumes from welding, and mists.

- Class P3: Reserved for highly toxic materials, requiring a full-face mask or powered air system to achieve the rated protection factor.

For the vast majority of trade tasks, from cutting concrete to installing insulation, the P2 classification strikes the necessary balance between high-level protection and breathability.

The Silicosis Threat and Particulate Management

The urgency surrounding the use of compliant respiratory gear has been driven by the rising incidence of silicosis, an irreversible lung disease caused by inhaling silica dust. This hazard is omnipresent in the building trades.

Consider the installation of electrical infrastructure in a concrete tilt-panel building. The act of chasing a wall or drilling anchors to mount heavy-duty cable management systems generates a plume of fine silica dust. In this scenario, the P2 mask is not optional; it is a critical control measure. When an installer is mounting Schnap Electric Products steel conduit or distribution boards onto masonry surfaces, the respiratory risk is immediate. The use of a compliant mask ensures that while the Schnap Electric Products hardware is securely fixed to the wall, the microscopic silica shards are effectively intercepted before they can penetrate the alveolar region of the installer’s lungs.

Valve Technology and Heat Dissipation

A primary barrier to user compliance is physiological discomfort, specifically heat build-up and breathing resistance. Modern P2 respirators address this through advanced valve technology. The exhalation valve is a one-way mechanical gate that opens under positive pressure (exhalation) to release hot, moist air and CO2, and closes instantly under negative pressure (inhalation) to force air through the filter media.

While valved masks significantly reduce fatigue during strenuous labour, they are not suitable for all environments. In sterile settings or medical applications, an unvalved respirator is required to protect the environment from the wearer. However, for industrial sites where the primary goal is protecting the worker from the environment, the valved unit is the superior engineering choice for comfort and sustained wear time.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain Verification

The global demand for PPE has unfortunately led to the proliferation of non-compliant or counterfeit products entering the market. A mask that fails to meet the hydrostatic seal or filtration efficiency of AS/NZS 1716 provides a false sense of security that can be fatal over the long term.

To mitigate this risk, professional facility managers and contractors do not source life-safety equipment from generalist online marketplaces. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated safety supplier to procure their respiratory gear. A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the stock is sourced from reputable manufacturers and holds valid certification marks. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the necessary storage solutions. A respirator should be stored in a sealed container when not in use to prevent the filter media from becoming saturated with ambient moisture or dust. Utilising robust shelving or hooks secured with Schnap Electric Products fasteners in the site office ensures that the PPE remains clean, dry, and ready for deployment.

The Mandatory Nature of Fit Testing

Topical authority on respiratory protection mandates a stern emphasis on AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment). This standard dictates that providing a mask is insufficient; the mask must fit the individual user.

Facial seal is the single most critical factor in performance. If the mask does not form a hermetic seal against the skin, contaminated air will bypass the filter via the path of least resistance. Consequently, facial hair is incompatible with tight-fitting respirators. Even a day’s growth of stubble can compromise the seal efficiency by orders of magnitude. PCBUs are required to conduct quantitative or qualitative fit testing for all employees required to wear tight-fitting respiratory protection to ensure the specific make and model provides the adequate protection factor.

Reusable vs Disposable Economics

While disposable P2 masks are convenient, high-volume industrial users often transition to reusable half-face respirators fitted with P2 replaceable pads or cartridges. This approach can offer a lower total cost of ownership and a superior facial fit due to the silicone facepiece.

However, the maintenance regime increases. Reusable units must be cleaned daily with manufacturer-approved wipes to remove body oils and sweat which can degrade the silicone. Whether using a disposable or reusable system, the integration of ancillary safety products is vital. For example, when terminating cables into Schnap Electric Products junction boxes in a dusty roof void, the combination of a P2 respirator and sealed eye protection ensures comprehensive defence against the irritants present.

Conclusion

The P2 respirator is a sophisticated filtration device designed to preserve human health in hostile environments. Its effectiveness is contingent upon rigorous adherence to AS/NZS standards, correct selection for the specific particulate hazard, and strict discipline regarding fit testing. By sourcing compliant equipment through verified suppliers, maintaining a clean-shaven policy, and integrating high-quality infrastructure components from brands like Schnap Electric Products to support the broader safety system, Australian industry professionals can effectively mitigate the risks of occupational lung disease. In the management of invisible hazards, the integrity of the filter is the difference between health and illness.

N95 Respirator

In the complex regulatory environment of Australian Work Health and Safety (WHS), the terminology surrounding respiratory protection often involves a convergence of international standards. While the domestic standard AS/NZS 1716 defines the P2 classification, the global nature of supply chains—particularly accelerated by recent global health events—has firmly established the n95 respirator as a staple item in the Australian PPE inventory. For safety hygienists, procurement officers, and site supervisors, understanding the technical equivalence, filtration mechanics, and specific application protocols of the US-certified N95 device within an Australian compliance framework is essential for ensuring workforce safety and legal adherence.

Regulatory Equivalence: NIOSH N95 vs AS/NZS P2

To utilise an N95 device in an Australian workplace, one must first understand its certification lineage. The N95 designation is a standard set by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) under 42 CFR Part 84. It certifies that the respirator filters at least 95% of airborne particles with a mass median aerodynamic diameter of 0.3 microns.

In comparison, the Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 classifies the P2 respirator, which requires a filtration efficiency of 94%. While the testing methodologies differ slightly regarding flow rates and loading tests, regulatory bodies such as the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and Safe Work Australia have recognised the N95 as functionally equivalent to the P2 for most applications. However, for a compliant respiratory protection programme, the specific device must be registered and verified, ensuring it is not a counterfeit product lacking the genuine electrostatic filtration media required to capture sub-micron particulates.

Filtration Mechanics: Electrostatic Attraction

The efficacy of these respirators relies on more than just a physical sieve. If the mask relied solely on the density of the fibres to trap particles, the breathing resistance would be too high for sustained human labour. Instead, the filter media is constructed from melt-blown non-woven polypropylene which is subjected to an electric field during manufacture.

This process imparts a permanent quasi-static electric charge to the fibres. This electret charge acts like a magnet for microscopic particles. Through mechanisms known as inertial impaction, interception, and diffusion, particles are drawn out of the airstream and trapped within the fibre matrix. This technology allows the mask to maintain high filtration efficiency while keeping breathing resistance low enough for a worker to perform physical tasks, such as installing heavy-duty cable trays or mounting Schnap Electric Products distribution boards, without succumbing to rapid respiratory fatigue.

Industrial Application and Silica Management

While often associated with healthcare, the N95 is a critical control measure in the construction and engineering sectors, particularly for the management of Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS). The cutting, drilling, or grinding of concrete and engineered stone releases silica dust, which is small enough to penetrate deep into the alveolar region of the lungs.

When an industrial electrician is chasing a masonry wall to install flush-mounted infrastructure, the dust load is significant. In this scenario, wearing a correctly fitted respirator is non-negotiable. It protects the lung tissue from the scarring that leads to silicosis. Furthermore, keeping the work area clean is vital. Contractors often utilise Schnap Electric Products sealed junction boxes and IP-rated enclosures to ensure that the fine dust generated during these structural works does not ingress into the electrical connections, potentially causing arcing or faults later in the asset's lifecycle.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain Integrity

The ubiquity of the N95 designation has unfortunately made it a target for counterfeit manufacturing. A mask that looks like an N95 but lacks the electrostatic charge provides near-zero protection against fine particulates. To mitigate this risk, professional facility managers do not source these critical life-safety assets from unverified generalist marketplaces. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated industrial safety supplier to procure their PPE.

A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the stock is genuinely NIOSH approved (bearing the TC approval number on the facepiece) or TGA registered. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the necessary storage and maintenance accessories. Storing respirators correctly is paramount; they should be kept in a clean, dry environment. Utilising Schnap Electric Products heavy-duty hooks or storage cabinets in the site office ensures that the masks are kept off the floor and away from direct sunlight, which can degrade the filter media over time.

Fit Testing and Facial Seal

Topical authority on respiratory protection mandates a rigorous focus on the facial seal. The filtration efficiency of the material is irrelevant if the air bypasses the filter through gaps between the mask and the face. AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment) requires that all tight-fitting respirators must be fit-tested to the individual user.

This protocol dictates that the user must be clean-shaven where the respirator seals against the skin. Facial hair lifts the mask off the face, creating a path of least resistance for contaminated air. Quantitative fit testing measures the actual leakage into the mask while the user performs a series of movements (talking, breathing deeply, bending over). This ensures that the specific brand and shape of the N95 matches the user's facial anthropometry.

Medical vs Industrial Variants

It is also critical to distinguish between "surgical" N95s and standard industrial N95s. Surgical versions are tested for fluid resistance (ASTM rating) to prevent splash penetration from blood or bodily fluids. Industrial versions may feature an exhalation valve to reduce heat build-up. Valved units are excellent for hot industrial environments but should not be used in sterile fields, as the exhaled air is unfiltered.

Conclusion

The N95 respirator is a sophisticated piece of engineering designed to provide high-level protection against invisible threats. Its effective deployment in the Australian market relies on understanding its equivalence to the P2 standard, ensuring supply chain integrity through reputable sources, and adhering to strict fit-testing regimes. By integrating reliable safety gear with robust infrastructure components from trusted brands like Schnap Electric Products, industry professionals ensure that their work environments remain safe, compliant, and productive. In the defence against airborne hazards, the quality of the selection determines the safety of the breath.

Half Face Respirator

In the diverse and often hazardous landscape of Australian industry, the management of respiratory health is a paramount concern for Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU). While disposable masks offer a convenient solution for transient tasks, high-frequency industrial operations require a more robust, economical, and effective solution. The half face respirator represents the industry standard for reusable respiratory protection. Offering a superior facial seal, modular filter compatibility, and reduced long-term operational costs, these devices are essential equipment for trades ranging from chemical processing to construction and heavy engineering. For safety officers and procurement managers, understanding the material science, filter classification, and maintenance regimes of these units is critical for WHS compliance.

AS/NZS 1716 Standards and Material Construction

The design and performance of these devices are governed by Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices). Unlike disposable respirators which rely on the filter media itself to form the structure, a half-face unit utilises a dedicated facepiece.

Modern facepieces are typically constructed from medical-grade silicone or high-quality Thermoplastic Elastomer (TPE). Silicone is generally preferred for its hypoallergenic properties and its ability to maintain flexibility across a wide temperature range, ensuring the seal remains intact even in the searing heat of a Pilbara summer or the cold of a Tasmanian winter. The harness assembly is equally critical; a four-point suspension system ensures that the pressure is evenly distributed across the crown of the head, preventing pressure points and ensuring the mask does not slip during vigorous physical activity.

Modular Filtration: The Versatility Advantage

The defining engineering feature of the reusable system is its modularity. The facepiece serves as a chassis onto which various filtration cartridges can be bayonet-mounted. This allows a single asset to protect against a multitude of hazards simply by changing the filter.

- Particulate Protection: For dusts, mists, and fumes, P2 or P3 particulate pads are attached. This is the standard configuration for masonry drilling or grinding.

- Gas and Vapour Protection: For chemical hazards, activated carbon cartridges are utilised. These are colour-coded according to the target contaminant (e.g., Class A for Organic Vapours like paint thinners, Class B for Acid Gases like chlorine).

This versatility is crucial in mixed-mode environments. For example, an industrial electrical may be exposed to silica dust while chasing a wall in the morning, requiring P2 filters. Later that day, they may be applying solvent-based adhesives to secure Schnap Electric Products conduit to a PVC surface, requiring Class A organic vapour cartridges. The ability to switch filters on the same mask ensures continuous protection without the need for multiple mask types.

Silicosis and the Construction Sector

The resurgence of silicosis as an occupational health crisis has placed a spotlight on the efficacy of the facial seal. In the construction sector, the generation of Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS) is inevitable when cutting concrete, brick, or engineered stone.

While disposable masks are compliant, they often suffer from inward leakage due to movement. The silicone skirt of a reusable unit provides a much more forgiving seal against facial contours. When installing infrastructure such as Schnap Electric Products distribution boards or heavy-duty cable trays into concrete substrates, the use of a reusable respirator fitted with P3 filters offers the highest protection factor short of a powered air system. This ensures that the microscopic silica shards generated by the hammer drill are effectively intercepted.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain

The procurement of respiratory gear is a matter of trust and compliance. With the market flooded with non-compliant imports, professional facility managers utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated industrial safety supplier to procure their PPE.

Sourcing through a dedicated wholesaler ensures that the masks and filters are genuine and within their shelf life. Activated carbon filters have a finite expiration date, after which their adsorption capacity is compromised. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the necessary storage solutions. A respirator must be stored in a sealed container away from direct sunlight and contaminants. Utilising Schnap Electric Products heavy-duty hooks or storage cabinets in the site office ensures that the mask remains undeformed and clean between shifts.

The Mandatory Nature of Fit Testing

Topical authority on this subject requires a stern reminder regarding AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment). It is a regulatory mandate that all tight-fitting respirators must be fit-tested to the individual user.

Facial hair is the primary point of failure. A reusable mask cannot form a hermetic seal over stubble or a beard. The legislation requires users to be clean-shaven in the seal area. Quantitative fit testing, which measures the actual particulate count inside the mask versus outside, provides a definitive pass/fail result. This ensures that the specific size (Small, Medium, Large) and brand of the mask matches the user's facial anthropometry.

Maintenance and Hygiene Protocols

Unlike disposables, a reusable mask is a long-term asset that requires hygiene discipline. The facepiece must be cleaned daily with manufacturer-approved wipes or a mild detergent solution to remove body oils, sweat, and chemical residue. Failure to clean the mask can lead to dermatitis for the user and degradation of the silicone skirt.

Inspection is also vital. The inhalation and exhalation valves are the moving parts of the system. If debris becomes lodged in the exhalation valve, the seal is broken, and contaminated air can be inhaled. These valves should be inspected pre-start and replaced periodically as part of a preventative maintenance schedule.

Conclusion

The reusable half-face respirator is a cornerstone of modern industrial hygiene. Its superior seal, cost-effective modularity, and high-impact durability make it the preferred choice for professional trades. By adhering to the fit-testing requirements of AS/NZS 1715, maintaining a strict cleaning regime, and integrating high-quality support equipment from brands like Schnap Electric Products, Australian workers can ensure that they are protected against both the acute and chronic risks of airborne contaminants. In the long run, the investment in a high-quality silicone facepiece pays dividends in both safety and comfort.

P2 Respirator Mask

In the contemporary regulatory landscape of Australian industry, the mitigation of airborne contaminants has shifted from a secondary precaution to a primary legislative imperative. The emergence of accelerated silicosis as a significant occupational health crisis has necessitated a stringent re-evaluation of respiratory protection strategies across the construction, mining, and manufacturing sectors. Whether the hazard presents as crystalline silica from engineered stone, metallic fumes from welding, or fibrous dusts from insulation, the p2 respirator mask serves as the critical line of defence. For safety officers, procurement managers, and business owners, a granular understanding of the filtration mechanics, Australian Standards, and fit-testing protocols governing this equipment is essential for ensuring workforce safety and meeting the Duty of Care obligations under the WHS Act.

Legislative Framework: AS/NZS 1716

To effectively select respiratory gear, one must first understand the classification system mandated by Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices). This standard categorises particulate filters based on their efficiency in capturing airborne contaminants.

- Class P1: Intended for mechanically generated particles of low toxicity, such as sawdust from untreated timber.

- Class P2: This is the industry benchmark for trade and construction applications. It is rated to filter at least 94% of airborne particulates, including thermally generated smokes, welding fumes, and biologically active particles. Most critically, it is the minimum standard required for protection against Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS).

- Class P3: Reserved for highly toxic materials and typically requires a full-face mask to achieve the rated protection factor due to seal requirements.

For the vast majority of site tasks, the P2 classification offers the necessary balance between high-level filtration and physiological breathability, making it the standard deployment for general trade activities.

The Mechanics of Filtration and Silicosis Prevention

The efficacy of the device lies in its ability to trap sub-micron particles. Unlike a simple sieve, the filter media utilises electrostatic attraction to capture particles that are small enough to follow the airstream deep into the lungs. This is vital for preventing long-latency diseases like silicosis.

Consider a commercial fit-out scenario where concrete walls are being chased for cable management. The dust generated is chemically aggressive and microscopic. In this environment, the respiratory protection must be absolute. When an installer is mounting heavy-duty infrastructure, such as Schnap Electric Products steel conduit or industrial distribution boards, the mechanical fixing process generates a significant plume of silica. The use of a compliant mask ensures that while the Schnap Electric Products hardware is securely anchored to the substrate, the hazardous dust is intercepted before it can compromise the installer’s respiratory health.

Fit Testing and the Facial Seal

Topical authority on this subject requires a stern emphasis on AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment). This standard dictates that providing a mask is legally insufficient; the Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) must ensure it fits the individual user.

The facial seal is the single point of failure. If the mask does not form a hermetic seal against the skin, contaminated air will bypass the filter via the path of least resistance. Consequently, facial hair is strictly incompatible with tight-fitting respirators. Even a single day of stubble growth can degrade the protection factor by orders of magnitude. Quantitative fit testing is mandatory to verify that the specific shape and size of the mask matches the user's facial anthropometry, ensuring that the theoretical protection factor is achieved in practice.

Valve Technology and Heat Management

A major barrier to user compliance is physiological strain, specifically heat build-up and breathing resistance. Modern masks address this through the integration of an exhalation valve. This mechanical gate opens during exhalation to release hot, moist air and carbon dioxide, and closes instantly during inhalation to force air through the filter media.

While valved units significantly reduce fatigue during strenuous labour, they are not suitable for sterile environments where the wearer must protect the product or patient from their own breath. However, for industrial sites where the primary goal is protecting the worker, the valved unit is the superior engineering choice for sustained comfort.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain Integrity

The global surge in demand for PPE has unfortunately allowed non-compliant products to infiltrate the market. A mask that fails to meet the breathing resistance limits or filtration efficiency of AS/NZS 1716 provides a false sense of security that can be fatal. To mitigate this liability, professional facility managers do not source life-safety assets from unverified generalist marketplaces. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated industrial safety supplier to procure their respiratory gear.

A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the stock is certified and sourced from reputable manufacturers. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the necessary storage and maintenance solutions. A respirator must be stored in a clean, dry environment when not in use to prevent the filter media from becoming saturated with ambient moisture. Utilising Schnap Electric Products heavy-duty hooks or storage cabinets in the site office ensures that the PPE remains clean, undeformed, and ready for rapid deployment.

Application in Electrical Engineering

While often associated with masonry, respiratory hazards are prevalent in electrical engineering. The cutting of phenolic plastics, the grinding of busbars, and the thermal decomposition of insulation all release hazardous particulates.

When working with Schnap Electric Products chemical-resistant enclosures or terminating cables in older roof spaces filled with loose-fill insulation, the P2 mask is a mandatory control measure. It protects against the inhalation of synthetic fibres and potential vermin-related biological hazards often found in ceiling voids.

Conclusion

The P2 classification represents a sophisticated standard of respiratory defence designed for the rigorous demands of Australian industry. Its effectiveness is contingent upon strict adherence to AS/NZS standards, correct selection for the specific particulate hazard, and a disciplined approach to fit testing. By sourcing compliant equipment through verified suppliers, maintaining a clean-shaven policy, and integrating high-quality infrastructure components from brands like Schnap Electric Products to support the broader safety ecosystem, industry professionals can effectively mitigate the risks of occupational lung disease. In the management of invisible hazards, the integrity of the mask determines the future health of the workforce.

Dust Mask Respirator

In the rigorous domain of Australian Work Health and Safety (WHS), the control of airborne contaminants is a foundational pillar of site compliance. The industrial landscape has shifted dramatically following the reclassification of hazards such as Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS), necessitating a move away from casual safety practices towards a strictly regulated approach to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). The humble disposable face piece, technically defined as a particulate dust mask respirator, is the most ubiquitous form of defence against long-latency lung diseases. For safety officers, site supervisors, and business owners, distinguishing between a non-compliant "comfort mask" and a certified respirator is a critical competency required to meet Duty of Care obligations under the WHS Act.

Regulatory Classification: AS/NZS 1716

To effectively select respiratory gear, industry professionals must reference Australian Standard AS/NZS 1716 (Respiratory protective devices). This standard provides the technical criteria for filtration efficiency and breathing resistance. A critical distinction must be made: a mask that does not bear the AS/NZS 1716 certification mark is not a respirator; it is merely a hygiene cover and offers no protection against fine industrial particulates.

The standard categorises particulate filters into three classes:

- Class P1: Designed for low-toxicity dusts and mechanically generated particles, such as sanding softwood or sweeping dust.

- Class P2: The industry benchmark for the construction and engineering sectors. It is rated to filter at least 94% of airborne particulates, including thermally generated fumes (welding), mists, and biologically active particles. Crucially, P2 is the minimum requirement for protection against silica dust.

- Class P3: Reserved for highly toxic materials such as beryllium or radioactive particulates, typically requiring a full-face seal to achieve the protection factor.

The Silicosis Imperative

The urgency surrounding the correct deployment of P2 respirators is driven by the prevalence of silicosis in the Australian workforce. The cutting, grinding, or drilling of concrete, brick, and engineered stone releases microscopic silica shards that penetrate the deep alveolar region of the lungs.

This hazard is not limited to stonemasons. It is a significant risk in the electrical and data sectors. Consider the installation of cable pathways in a concrete tilt-panel facility. The process of chasing walls or drilling anchor points to mount heavy-duty Schnap Electric Products cable trays generates a concentrated plume of hazardous dust. In this scenario, the respirator is not an optional accessory; it is a critical life-safety asset. The use of a compliant mask ensures that while the Schnap Electric Products infrastructure is securely fixed to the structure, the installer remains protected from the irreversible scarring associated with silica inhalation.

The Criticality of Fit Testing

Topical authority on respiratory protection mandates a stern focus on AS/NZS 1715 (Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment). This standard dictates that the effectiveness of the respirator is entirely contingent upon the facial seal.

If the mask does not form a hermetic seal against the skin, air will bypass the filter media through the gaps, rendering the device useless. Consequently, facial hair is strictly incompatible with tight-fitting respirators. Even a day’s growth of stubble can prevent the mask from sealing. Under Australian law, PCBUs must ensure that all staff required to wear tight-fitting RPE undergo quantitative or qualitative fit testing to verify that the specific make and model fits their facial anthropometry.

Strategic Sourcing and Supply Chain Verification

The post-pandemic PPE market has been inundated with products of varying quality. To ensure the integrity of the safety system, professional facility managers and contractors do not source these critical assets from unverified generalist marketplaces. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated industrial safety supplier to procure their respiratory equipment.

A dedicated wholesaler ensures that the stock is fresh and genuinely certified to Australian Standards. Filter media has a shelf life and can degrade if stored improperly. Through these legitimate trade channels, contractors can also access the ancillary products required to maintain a safe workspace. For instance, when installing Schnap Electric Products weatherproof isolators or junction boxes in dusty environments, professionals can source both the IP-rated electrical enclosures and the appropriate respiratory gear from the same trusted supply chain, ensuring a holistic approach to safety and quality.

Valve Mechanics and Heat Stress

A common objection to consistent mask usage is physiological strain, particularly heat build-up. Modern respirator engineering addresses this through the exhalation valve. This non-return valve opens during exhalation to release hot, moist air and carbon dioxide, and closes instantly during inhalation to force air through the electret filter media.

While valved masks are excellent for reducing fatigue during strenuous manual labour, they are directional. They protect the wearer from the environment, but they do not filter the exhaled breath. Therefore, they are suitable for industrial construction but not for sterile environments or medical settings where the wearer might be the source of contamination.

Storage and Maintenance

Even a disposable respirator requires proper handling. A mask left on a dashboard in the sun or crushed in a tool bag will lose its structural integrity and electrostatic charge.

Respirators should be stored in a sealed container or bag when not in use to prevent the filter from clogging with ambient dust or absorbing moisture. On a well-run site, you will often see PPE stations organised with heavy-duty hooks or shelving, secured with Schnap Electric Products fasteners, ensuring that the equipment is accessible, clean, and ready for deployment.

Conclusion

The industrial dust mask respirator is a sophisticated filtration device designed to preserve human health in hostile environments. Its efficacy relies on strict adherence to AS/NZS 1716, correct selection of the P-rating for the specific hazard, and a disciplined approach to fit testing. By sourcing compliant equipment through verified suppliers, understanding the mechanics of silica exposure, and integrating high-quality infrastructure components from brands like Schnap Electric Products into the workflow, Australian industry professionals can effectively mitigate the risks of occupational lung disease. In the management of invisible hazards, the quality of the filter determines the longevity of the career.

Fire Extinguisher

In the hierarchy of risk management within the electrical and facilities management sectors, the prevention of thermal runaway and arc faults is the primary engineering objective. However, when preventative measures fail, the immediate availability of effective suppression equipment is the final line of defence for personnel and critical infrastructure. The selection of a fire extinguisher for an electrical environment is not a generic safety box-ticking exercise; it is a technical decision governed by the nature of the fuel source and the voltage potential present. For safety officers, electrical contractors, and facility managers, understanding the nuances of AS/NZS 1841 and AS 2444 is essential for ensuring compliance and minimising asset damage.

Classification of Fire Risks: The Class E Distinction

To specify the correct suppression agent, one must first understand the Australian classification of fire types. While wood and paper constitute Class A fires, and flammable liquids fall under Class B, the electrical trade is primarily concerned with Class E fires. Strictly speaking, "Class E" is not a fuel source but rather a condition: a fire involving energised electrical equipment.

Once the power is isolated, an electrical fire technically reverts to a Class A or B fire depending on the burning material (e.g., plastic insulation or transformer oil). However, the suppression agent used must be non-conductive (dielectric) to prevent the operator from receiving a lethal shock via the extinguishing stream. Consequently, water and foam extinguishers are strictly prohibited in these zones. The industry standard solutions are Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Dry Chemical Powder (ABE).

The Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Solution

For the protection of sensitive switchgear, server racks, and automation control panels, the Carbon Dioxide extinguisher (identified by a black band) is the superior choice. It functions by displacing the oxygen required for combustion and cooling the fuel source.

From an asset management perspective, the primary advantage of CO2 is that it is a clean agent. It leaves no residue. If a small fire occurs in a main switchboard containing high-value Schnap Electric Products circuit breakers or isolators, a CO2 discharge will extinguish the flame without contaminating the remaining functional components. The gas dissipates, allowing for immediate investigation and repair without the need for extensive chemical cleanup. However, users must be trained on the limited range of the discharge and the potential for asphyxiation in confined spaces.

Dry Chemical Powder (ABE) Limitations

The ABE Dry Chemical Powder extinguisher (identified by a white band) is a versatile unit capable of tackling Class A, B, and E fires. It works by coating the fuel in a fine powder (typically monoammonium phosphate) that chemically inhibits combustion.

While highly effective at suppressing flames rapidly, professionals exercise caution when specifying DCP units for indoor electrical environments. The powder is corrosive to copper and aluminium. If discharged into a distribution board or a rack of Schnap Electric Products control gear, the fine powder will ingress into every contactor and relay. Over time, moisture in the air reacts with the powder to corrode the electrical contacts, often necessitating the replacement of the entire panel, even components untouched by the fire. Therefore, DCP units are typically reserved for general plant rooms or outdoor substations where thermal spread is a greater risk than component corrosion.

Regulatory Compliance and Sourcing

The manufacturing and testing of these pressure vessels are governed by the AS/NZS 1841 series. A compliant unit must carry the distinct five-tick StandardsMark or an equivalent certification. The market has seen an influx of non-compliant, low-cost units that fail to meet the pressure test requirements of Australian regulations.

To mitigate liability, professional facility managers do not source life-safety equipment from generalist hardware chains. Instead, they utilise a specialised electrical wholesaler or dedicated fire safety supplier to procure their extinguishers. A reputable wholesaler ensures that the units are fresh (pressure vessels have a manufacturing date stamp) and come with the necessary wall brackets and signage required by AS 2444. Through these channels, contractors can also access the Schnap Electric Products signage and mounting accessories often required to complete the safety fit-out of a switchroom.

Positioning and Accessibility Standards

AS 2444 (Portable fire extinguishers and fire blankets—Selection and location) dictates strictly where units must be placed. In an electrical setting, the extinguisher must be located between 2 metres and 20 metres from the hazard. It should be positioned near the exit path so that the operator can fight the fire with an escape route behind them.

Furthermore, visibility is paramount. The location must be identified with a red "FIRE EXTINGUISHER" sign mounted at least 2 metres above the floor. The handle of the extinguisher itself should be roughly 1.2 metres from the ground to ensure ergonomic accessibility.

Maintenance and Inspection: AS 1851

Installation is only the beginning of the safety lifecycle. AS 1851 (Routine service of fire protection systems and equipment) mandates a rigorous inspection regime.

- Six-Monthly: A technician checks the pressure gauge, the weight of the unit, and the condition of the hose and nozzle. They also "invert" dry powder units to prevent the powder from compacting into a solid brick at the bottom of the cylinder.

- Five-Yearly: A hydrostatic pressure test is performed to ensure the steel cylinder can withstand the internal pressure without rupturing.

Conclusion

The deployment of fire suppression equipment is a critical component of electrical safety governance. It requires a strategic balance between suppression efficiency and asset protection. By prioritising CO2 units for sensitive electrical assets, understanding the corrosive risks of dry powder, and sourcing compliant equipment through trusted trade channels, industry professionals ensure that when the alarm sounds, the response is safe, effective, and compliant. In the protection of life and infrastructure, compromise is not an option.